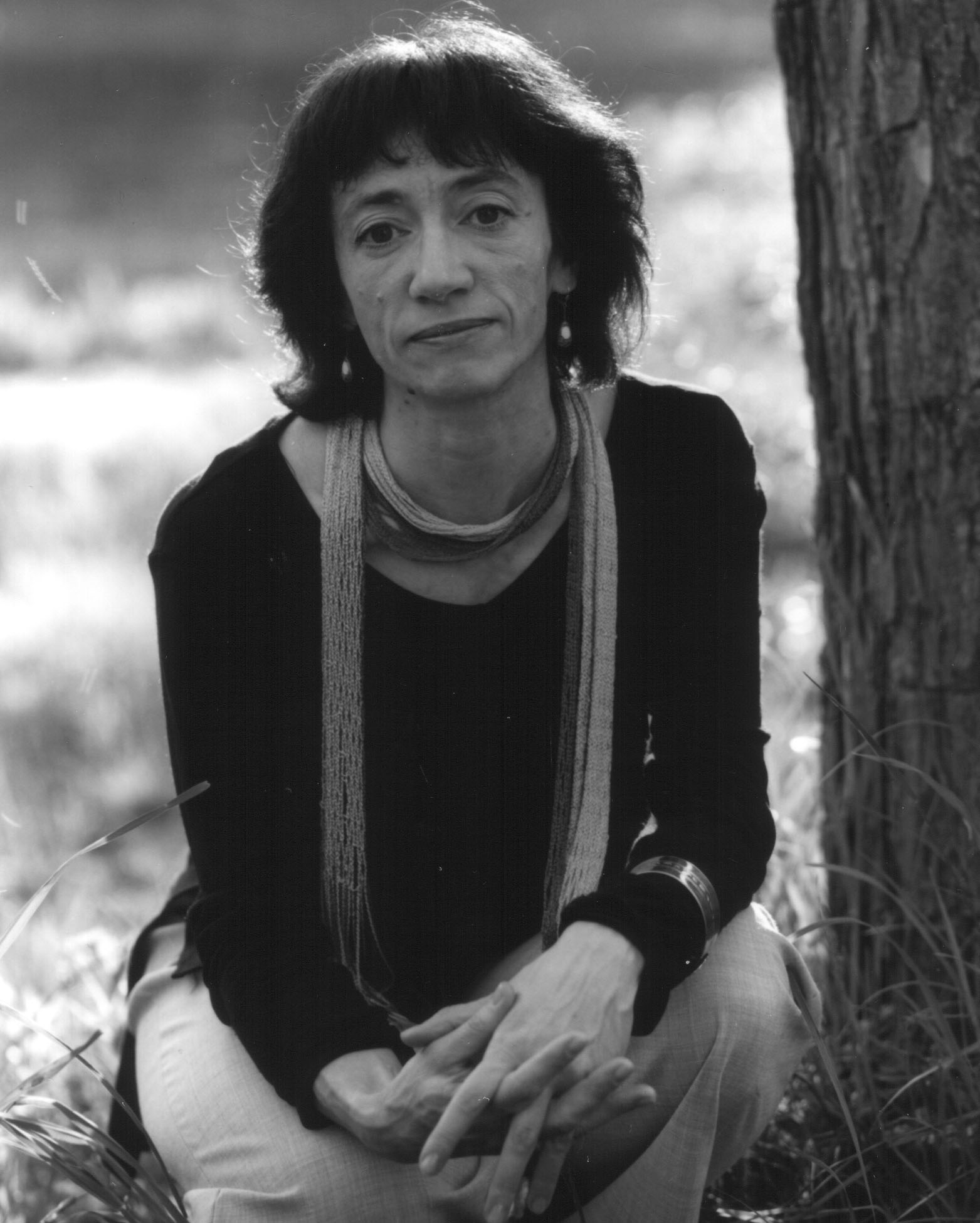

Always unexpected. Interview with composer Onutė Narbutaitė

- Dec. 22, 2022

Interviewed by Ona Jarmalavičiūtė

Onutė Narbutaitė is a paradoxical composer whose music slips away from the labels, jumps off the cultural shelves and leaves the listener in awe every time. The composer greets me in the kitchen of her home. “Now is not the time for me to talk,” she explains while brewing tea. “In fact, I spend a lot of time simply with myself.” The conversation begins with a confession of love for Vilnius – childhood memories from a dormitory near the Lithuanian National Martynas Mažvydas Library, the time of her life spent in the heart of the Old Town, living in a house close to a cemetery, listening to the bubbling of the Vilnelė and taking walks in the Bernardine Gardens. Later it turns out that both Vilnius and music are the only constants in her life.

In the interview, the composer shares her impressions of the premiere of her latest work, Otro río, reveals the long-term collaborations that have influenced her life, and speaks about the slow, complicated, multi-layered process of composing music. The latest recording is being presented at the moment, the Vespers composition Lapides, flores, nomina et sidera sung by the Aidija and the National M. K. Čiurlionis School of Arts choirs (artistic director Romualdas Gražinis).

How did you choose to lead a creative lifestyle?

That my life would revolve around the arts, in one form or another, was clear quite early on. In my adolescence and early youth, there was a wave of drawing: ink, gouache, I even bought oil paints, but after trying it I realized I should study it more seriously. I was always writing and to this day, both the visual arts and literature are very important fields of experiences and inspirations for me. There were all kinds of ideas. For the last two years at the Čiurlionis School of Arts, I studied composition with Bronius Kutavičius and got so involved that it was clear that if I was going to stay with music it would only be as a composer.

After my studies, by appointment, I taught music theory in Klaipėda for several years. When I returned, I thought – for a year I will be engaged in creativity but after that I’ll look for a job. Personal circumstances changed so that I remained ‘out of work’ until now. When you taste the freedom that could be achieved through creativity under the circumstances of the time, albeit conditionally, you no longer want to return to the previous rhythm of life. Although later I had various offers, at one point my professor, Julius Juzeliūnas, with all his characteristic persistence, pressed me to come to the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre to teach composition. I didn't give in because I looked at it responsibly, and by nature I am more of a one-tasker than a multi-tasker. That's how time flew by.

How would you describe your creative process?

I tend to work slowly, calmly. If I'm not working to commission, without a deadline, I can slow down terribly. I need a certain atmosphere for composing. Each piece has its own atmospheric field. Life itself doesn’t always allow us to be in it intensively. But different opuses dictate different time requirements, and it’s interesting that the writing time does not necessarily, or only very relatively, depend on the scope of the compositions or the duration of the works.

The creative process never begins with writing specific notes, it depends on the nature of the composition itself. The beginning can be a hard-to-name image or a very specific flash – usually something inspired by a much wider field than just sound. The flash can be a sound figure, a sound sensation, but it can also be inspired by a very specific visual experience, a combination of words, or some unexpected sensory tingle. When it comes to my large-scale lyrical compositions, the beginnings tend to be very complex, involving a lot of non-musical explorations.

When I start working, I have to have a fairly clear general vision of the form, a structural plan, especially in the case of large compositions. However, I am not scholastic and I trust my intuition, something may change along the way. There have been times, for example, in the first movement of the Second Symphony, that before starting work I wrote down a whole sequence of significantly changing harmony chords, which was very long, and I immediately predicted their proportional progression in time, and I actually followed it. It was suitable and convenient in that very specific case, but usually I don't prepare in such detail. I define a certain conditional mode, a possible sound field in which I will move and that's it. Even with such bare pre-arranged material as a chord sequence, you never know what will grow out of it.

So, on the one hand, the whole of the work is a piece of architecture, a compositional plan is important to me when creating. On the other hand, the language of my music is very detailed, especially dynamically; as the voices have their own individual dynamics or strokes, a certain uncertainty, a flickering impression is created. So when composing, I pay attention to both the details and the whole.

I usually specify that finer colour detailing later, already having the general image of the composition before my eyes. Then sometimes I change something, rewrite it or make notes. I do that revision before the rehearsals, and in the subsequent process there are only occasional cases of minor corrections related to fine-tuning the sound balance as a normal part of the live creative process. By the way, moments of conditional individual aleatorics often occur in my scores. There is also an attempt like Necklace, which simply can’t have two identical performance versions – it’s strung every time anew and can be performed in completely different instrumentations. So when I try to describe something, I include only some, perhaps the dominant part of the works, but something always slips out of those descriptions, doesn’t fit into the scheme.

It’s difficult to describe your work, it constantly surprises and changes. What’s your creative axis for yourself? Are there also commonalities among all these creative differences?

I don't know how much that music changes, my regular performers recognize it immediately when they pick up the new sheet music. But yes, looking at the entire path, you can find outwardly very different works. In the early works, the language was more ascetic, later there was more complexity, more openness to diverse expression and, as it were, connections of matter of different natures, more contextuality in various senses. Now, already moving down the mountain, I feel a kind of arch, a certain return to a more reduced expression, but already with a different experience, without rejecting it.

I feel quite independent. When various currents arise, in the sound of composers of a certain circle, common definitions often appear in the structures that are insurmountable and easily identifiable from the outside. By listening, you can sense what can be in the piece and what can't really be. Later you start to predict how the piece will end, what will come next. This is how niches are formed in the world, it is this clear definition that is associated with the recognition of the composer, and it’s convenient. But sometimes, after hearing one of the composer's works, you can already predict all the rest. After a while, that purity can become routine.

I’ve never changed in any planned way to break anyone's expectations. Change, if any, has happened naturally. It's true, I remember how in the first part of the Second Symphony I allowed myself to write such melodies that I even came close to what a group of colleagues labeled me in Lithuania, but which was never true until then – neo-romanticism. Apparently, I decided to finally adapt to it (she laughs). I remember a certain barrier in the subconscious, which I crossed because I intuitively felt: this is exactly what I need here. Of course, this was only one of the details of a large building. And it’s paradoxical that later this work, which premiered in Lithuania, received very positive evaluations – outside Lithuania. And, it seems, precisely because of the unpredictability of its progress.

After a concert in Vienna, during which the compositions Melody in the Olive Garden, The Creeper, Winterserenade and Mozartsommer were played, an Austrian-educated student could not accept the fact that all these works were written by the same person, he found them too different. It doesn't seem that way to me at all. On one occasion, I compared seemingly quite different scores from different creative periods and, to be honest, despite all the external differences in the sound material, I found a lot of internal commonalities, both in the flow of the whole and in the phrasing and detailing. There is some common characteristic breath, maybe something technically indefinable, atmospheric, but really co-existing. This is probably the axis you asked about – nature itself and the intuition that governs it.

What then could be the nature of Lithuanian-ness in music?

I think that the search for and consolidation of Lithuanian-ness was relevant at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Belonging to a certain culture is a matter of course. It works unconsciously and is often better felt and recognized from outside than inside. But the individual nature, experiences and interests of everyone are also very important in creativity. Today, the Lithuanian sound is usually associated with various manifestations of so-called Lithuanian minimalism, or at least we ourselves tend to form such an image. But I can quote how the well-known German critic Reinhard Schulz saw the Lithuanian music landscape 20 years ago in Süddeutsche Zeitung: “Lithuania is a unique country. (...) Unlike in Estonia or Latvia (...), here we will not find a homogeneous landscape of musical language. That language is more based on individuals and is oriented towards international techniques.” So everything is changing, and today both that landscape and the comparison with our neighbours would probably be completely different.

Indeed, in Lithuania there are no established strong circles and currents with unquestionable patents of good taste, and no pressure to obey them, as perhaps still exists in some countries. Like the need to belong to someone. In this sense, our composers can feel freer in their choices. But there is another side of the coin. The existence of the aforementioned ‘circles’, as well as deeper school traditions, on the one hand constrains and on the other, even by provoking to do the opposite, supports a level of quality.

Perhaps these days we can no longer divide music so simply by countries, currents or schools. There are more and more individual choices in music. But if we look back at history, distant or recent, we will not discover anything new – everything has always been determined by individuals themselves.

In mid-November, the premiere of your latest composition Otro río took place in Finland. What are your impressions?

Otro río is already the third piece I have written for the Ostrobothnian Chamber Orchestra (previously Sinfonia col triangolo (1996) and Was there a butterfly? (2013) - O.J.). This orchestra is fantastic. They reside in the small Finnish town of Kokkola, which has only about 50,000 inhabitants. But it’s the best chamber orchestra in the country, which has toured the world's biggest stages. Orchestra leader Juha Kangas was once a violinist and violist himself. He played in the Helsinki Symphony Orchestra, and later returned to his hometown and formed this orchestra. A couple of years ago, he retired from the position of artistic director of Ostrobothnian Chamber Orchestra, but every year he organizes programmes with the orchestra, new recordings are always released, and there is constant cooperation with the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra.

It is understood that he prepared the programme of the anniversary concert. Mr. Kangas is a very perceptive conductor, who skillfully reads the score, goes deep, and is extremely sensitive to all the nuances. He knows the possibilities of string instruments very well and has a lot of practice. And the orchestra plays everything from baroque to contemporary music. In 1995, in a double album of music from the Baltic countries, they recorded a number of Lithuanian works, by Bronius Kutavičius, Osvaldas Balakauskas, Antanas Rekašius, Mindaugas Urbaitis, Jurgis Juozapaitis and my Opus lugubre. They have performed almost all of my pieces for chamber orchestra, three of which have been recorded on CD. And the orchestra is able to give a vitality to every style, every piece, with its performance.

On that day (November twelfth - O.J.) fifty years ago, their first concert took place. As announced, the composers closest to them were included in the programme of the anniversary concert, and a new piece was commissioned for me. I accepted this as special trust and a great responsibility, which, of course, was not a relieving background when working. But I tried to distance myself from it, I wrote as the intuitive pull led me at the time. Otro río is not an occasion-oriented composition, it’s very far from any jubilation.

I have to admit, I was full of fear when I went to Finland, but after the first rehearsal it subsided a lot. In one episode of the piece, the music takes a risky approach to near-silence, which isn't accepted by every audience. Politicians and representatives of the city government were also sitting in the hall that evening – people who usually don’t go to concerts. During the quieter episodes, they might start coughing, flipping through the programmes, I was really afraid that would be the case. But it wasn't. One cough, another. After that there was complete silence for a long time, the entire full hall listened attentively. The reaction was strong.

The Ostrobothnian Chamber Orchestra played everything perfectly. Of course, I still have no distance, it’s hard to judge for myself how justified that reaction is, but I was glad I didn’t disappoint Mr. Kangas and the musicians. By the way, the Spanish title of the work comes from a line by Jorge Luis Borges, a fragment of which is quoted in the score as a motto: “El tiempo es otro río” – Time is another river.

As far as I know, this collective contributed significantly to the development of your career abroad?

Maybe not directly, but this collaboration, especially the first two recordings of my works released by the Ostrobonian Chamber Orchestra in Finland, really opened up some professional opportunities for me abroad. Those records contributed to the fact that in 2001-2002 Finlandia Records released an original series of four CDs, which became a kind of springboard into the wider world. This led to an invitation to the festival Aboa Musica in 2003, held in the Finnish city of Turku, which is dedicated only to two composers each year, one Finnish, one foreign. At that time I was ‘paired’ with Einojuhani Rautavaara, seven of my works were performed, including the Second Symphony. Even when I was commissioned to compose a piece for the Bavarian Radio Orchestra, for the Musica Viva concert series, I found an echo of that Ostrobothnian connection. Musica Viva is the oldest and most influential contemporary music series in Germany, with Igor Stravinsky, Olivier Messiaen and later the entire 20th century avant-garde ring. It turned out that one of the organizers of the then Musica Viva programme discovered my music precisely through the recordings of the Ostrobothnian Chamber Orchestra. Although I had already realized five German commissions, including the hour-long Tres Dei Matris Symphoniae for choir and orchestra, in this case the connection was fateful.

How would you compare your creative work opportunities in Lithuania and abroad?

I can't compare. I've always lived only in Lithuania; from my experiences abroad I can only guess what it would be like. You can write music anywhere, anything else is possible for your music to live: performance, commissions, dissemination, reviews. In these aspects, Lithuania is not the best place for contemporary music. There have always been and are people who spend a lot of time and effort to make a change, there are new music festivals that attract a lot of listeners. But where organized structures and financial capacity are needed, the changes are very small. For example, due to the specifics of funding, commissions for works are submitted very late, which encourages the superficiality of the result. And that funding is probably most abundantly distributed for one-day events. There’s a certain levelling, an erosion of quality, which the Lithuanian soil is very favourable for. A lot is determined by the general mentality of the wider society, even in a more intellectual environment, only in the case of individual people, there is some need and perception for more than just relaxation or background music. Compared to all other fields of art, we are on the furthest frontier or even the fringes of this mentality.

Do you only compose by commission?

This is a myth. Yes, I’ve received them, and from the beginning of independence until now, I have written twenty-one works commissioned by festivals or other institutions, four of which were commissioned in Lithuania. But before independence there were no commissions at all. I wrote what was on my mind, there’s a whole series of works that appeared at the request of the artists. It was only after the 1990s that foreign opportunities opened up and I began to receive various offers. In the long run, quite a few had to be abandoned due to existing commitments or other priorities. I also missed some rare opportunities, but you can't cover everything. Anyway, it always was and is this way. For example, I wrote the Second Symphony without any commission and without any royalties, interspersed between other responsibilities. Now it seems that I prefer to surrender only to my own slow time, without stress or deadlines.

Currently, the latest recording of your composition Lapides, flores, nomina et sidera is being released in Lithuania. How was this piece born?

In 2008, World Music Days took place in Vilnius. This commission was the idea of the curator Lieven Bertels. The piece is dedicated to All Souls’ Day, when concerts are not usually held. The original idea was to perform this piece in various open spaces in the Old Town: many choirs would sing the same piece in different places. However, knowing our usual November weather, such an idea didn't seem entirely realistic, so from the beginning I thought about a solution that could be implemented in churches. The main condition was the simplicity of the music – it should be able to be performed by choirs of various levels. Admittedly, I didn’t fulfil this condition perfectly, although I tried. However, two non-professional choirs participated in the premiere, in the Vilnius University and Bernardin parishes, and they conquered the piece. On my own initiative, I also added several instruments, the piccolo flute, trumpet, trombone and drum.

My inner state at the time was very responsive to this commission, as it was the first year after my mother's death. In addition, Vespers had become one of the symbols of Vilnius even in my childhood. During the Soviet era, it was a sacred thing to go and light candles on the graves of Jonas Basanavičius, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis and others in the Rasa Cemetery, which was full of security guards on those occasions. So I thought least about the context of the contemporary music festival. In the annotation, I talk about the discretion of authorship. I really tried to create something that could naturally blend in and become its own in the more diverse community of Vilnius.

As a supplement to that project and a modified implementation of the original outdoor performance idea, I wrote an unsolicited evening piece, Cantio vespertina. It was performed at the Bernardine Cemetery on All Saints' Eve. The element connecting those two compositions is the motif of Requiem aeternam; its sound is reminiscent of a lullaby. The language here is really simple, the material can easily be memorized and sung in the dark, without notes. I remember it was already dark, only the flickering of candles, the monotonous sound of choirs arranged in the cemetery, the interweaving motif of piccolo flutes. The weather was rarely good – there was no wind, it wasn’t cold. It was a really special atmosphere. Judging by the reactions of the listeners, we really succeeded in that cemetery project, it's a pity it remained a one-off event and was not recorded in any way.

How would you describe the composition Lapides, flores, nomina et sidera?

I have called it not so much ‘autonomous music’ as a ‘composition of sung words’. It’s basically four litanies of stones, flowers, names and constellations. For me, this composition is about everything – the earth, the universe, where we are, who we are.

I was also interested in the liturgical traditions of Vespers. I turned on the liturgical aspect in my own way, not only through the Litany of All Saints but also through other texts repeated in all parts – Beati misericordes, psalms, the responsorium Libera me, which I use in an authentic ancient sound, Requiem aeternam. I treated the liturgical texts as signs. They are so famous and capacious that a couple of lines are enough. In the first and last part of the psalm, Hebrew language also sounds. It is also a capacious sign and allusion in the context of Vilnius.

I was also thinking about the hidden convocation with Vespers processions. Although the choir stands still, a kind of procession takes place in the music itself. Each part has not only a different expression of the dominant sound but also the same repetitive elements. The premiere was performed by seven choirs in seven Vilnius churches. People who tried to go between the churches could hear something different every time, from stones to flowers or from names to stars, but everywhere they heard the same repetitive sound.

I joke that I wrote Latin poetry for this opus. But in fact I picked the Latin names of natural objects myself and arranged them like lines in a poem, suitable for the repetitive rhythm of singing. Together, I connected them with meaning and hid all kinds of signs inside. Let the semioticians search. I personally find a lot of poetry in those lists. My father is a geologist, and I was able to consult on issues of geological objects with him.

And I expanded the Litany of All Saints to the maximum, I wanted a list of names as long as possible, repetition as long as possible. I allowed myself to include a couple of holy women, closer to our times – St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross and St. Sister Faustina Kovalska. Behind these two names are very different personalities and biographies. Each of them brings its own meaningful signs. This whole composition is framed by the recurring motif of mercy.

What are your thoughts while waiting for the release of the recording?

This recording was an initiative of the Aidija choir. I didn't find out until much later that there would be a recording. Back in 2008, on All Souls' Day, Aidija performed this composition at St. Ignatius Church, and this year the same artists recorded this piece in the same place. It was Aidija with the choir of the M. K. Čiurlionis School of Arts that were also participants in the performance of Cantio vespertina at the Bernardinai Cemetery.

I am extremely grateful to all the performers, the instrumentalists, the choirs and the artistic director Romualdas Gražinis. Our cooperation is long-term, based on deep trust, we have many memorable joint experiences. I know how much care, work, depth and heart went into the production of this record.

„Lapides, flores, nomina et sidera“ is available on musiclithuania.com and bandcamp.com. The release of the album was funded by the Lithuanian Council for Culture and the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania.