Mykolas KATKUS | A Comfortable Wooden Overcoat: Rock Music in Lithuania

That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange aeons even death may die.

H.P. Lovecraft, Necronomicon

When a music magazine editor asks a rock band vocalist[1] to write a review about rock music and suggests The Death of Rock title for it, it says a lot. Especially since the Lithuanian rock music scene is currently enjoying the undoubtedly largest revival since the legendary Rock March, the popular festival-rally that contributed to the dismantling of the Soviet Union in 1987–1989.

The truth is that rock music scene was never particularly dynamic in Lithuania, however, just like in the quote by the horror writer Howard Phillip Lovecraft above, it was never actually dead. Rather, it was trying to outlive death itself. And this is where the story begins.

The burnt movement

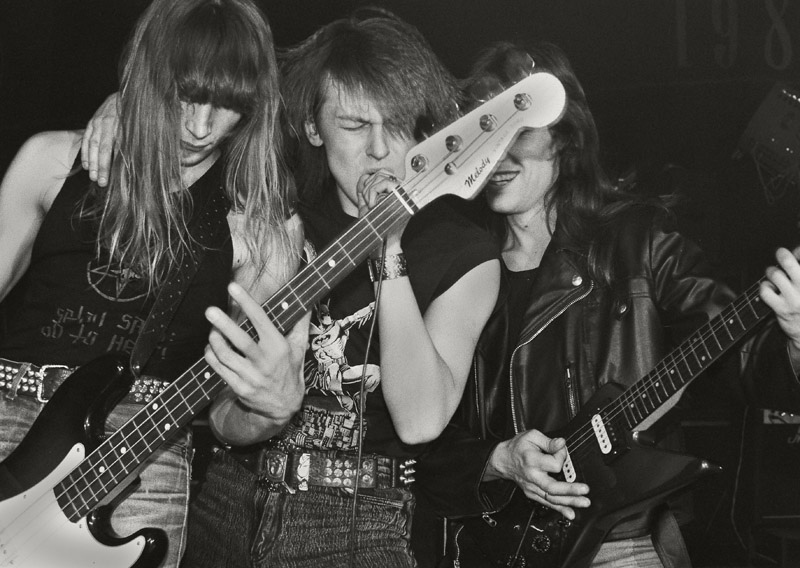

“In Lithuania, rock music was killed in a cradle – after Romas Kalanta set himself aflame in 1972 and the youth uprising in Kaunas was crushed, all talented rock bands of the time were driven away,” wrote the renowned Lithuanian philosopher (and rock music lover) Leonidas Donskis. Romas Kalanta was a Kaunas hippy who self-immolated in a protest against the Soviet regime and his act attracted the KGB’s attention to all the countercultures of that time. Rock musicians in Latvia, Estonia and Russia were not persecuted; they had space to express themselves in and an entire wave of performers who followed the western trends or interpreted them in their way was formed there. Instead of such wave, Lithuania had VIAs – vocal and instrumental ensembles approved by the Philharmonic Society and performing arranged works by foreign performers or local professional composers. The function of such ensembles was to service restaurants, cultural centres and community events; their repertoire was selected by their artistic directors who, in their turn, made sure everything aligned with ideological structures. It is no wonder then that the main source of inspiration for those musicians was pop music or rock standards reduced to saccharine sound, while rock music movement, without rehearsal spaces or support, remained exclusively in the underground, often persecuted by the censorship. There was more energy in the sung poetry movement led by the actor Vytautas Kernagis or in jazz, in which the Ganelin / Tarasov / Chekasin Trio formed the core of the intellectual entertainment music. In 1985, during Gorbachev’s ‘perestroika’, the Soviet Union opened up to the western culture, at the same time driving the change within. There was a sudden surge in newly formed (often simply newly legalised) student rock music bands. The art rock band Antis with the charismatic leader Algirdas Kaušpėdas proclaiming political declarations, the hard rock band SBS, Tigro Metai, Katedra and Volis, the punk band Už Tėvynę, the romantic boy band Foje with Andrius Mamontovas at its lead and the band from Šiauliai BIX who played the funk rock that verged on hard rock – those were the most well-known but not the only names. At that time, rock music was for the wide society essentially a previously unheard set of sounds that hit their ears together with the discussions on economy, independence and hidden history. In general, the need for the spiritual that was felt in Lithuania during its quest for independence at that time was tremendous: alongside the ironic songs about ‘apparatchiks’ by Antis, euphoric audiences also gathered to listen to Bernardas Brazdžionis’ poetry, publicly read philosophical texts and long talks about history. The peak of rock renaissance was the festival Rock March. Its second edition saw the popular politician and philosopher of the time Arvydas Juozaitis joining the musicians of BIX and Antis on the tour – he held talks about environmental protection, bringing the festival almost close to Live Aid. An important part of that culture became the film The Children from the Hotel America released in 1990 and symbolically transporting to the events of 1972 when teenagers who listened to rock on the Luxembourg radio were divided by the militia and the movement died.The decade of enthusiasts

The Rock March and the revival of the rock culture that followed did not last long. After the restoration of independence in 1990, the society quickly grew bored of rallies and marches, as massive changes in the economy left no one unaffected and music was far from the first thing on people’s minds. Out of all the heroes of the Rock March, only Foje were able to convert their political glory into long-term popularity. The leader of Antis Algirdas Kaušpėdas turned to politics, Katedra dissolved and BIX gradually became a band that plays for an increasingly narrow circle of rock fans. Radio stations that were beginning to understand their audiences better and better, played less and less rock, while the rock musicians turned to producers, forgot their guitars and started experimenting with pop and rap beats instead.

Although Lithuania had functioning radio stations and cable channels that showed MTV, it remained completely untouched by grunge, post-grunge and punk rock revolutions that shook the international musical scene. The most prominent rock bands of the new era between 1991 and 1996 were Šiaurės Kryptis, a student band inspired by post-punk, the goths Siela and Mano Juodoji Sesuo, psychedelic experiments by Algis Greitai and rock heroes from the regions other than Vilnius – Afiša from Ukmergė and Airija from Alytus.The challenge to synchronise Lithuania with the western music culture was accepted by the ambitious music publishing company Bomba. This company that has dominated Lithuanian musical market for a decade came to exist from the music idealist and promoter Dovydas Bluvšteinas’ publishing company Zona. Having quickly outgrown their founder, the energetic managers of Bomba started looking for new and modern rock and pop music, opening music stores, publishing magazines that promoted such styles and creating music programmes. They were basically building all the music infrastructure they needed from scratch. In the rock area, undoubtedly the greatest discoveries by Bomba were two bands by Russian-speaking youngsters from Vilnius that for the first time, only with about a year’s delay, echoed the musical trends of the time – Lemon Joy and Biplan, at that time enthusiastically titled the Suede and Blur of Lithuania. Shining in the punk rock alternative that by then had been born at last were the bands Dr. Green and Lipnūs Macharadžos Pirštai.

However, with the exception of several cases (the Biplan debut entitled Braškės was very popular and albums by the guitar rap band ŽAS sold well) rock did not pay off. There were almost no festivals, rock stages were often improvised and unprofitable, the sales of cassettes and CDs were considerably lower than those of pop music, while the biggest market was the publishing of wedding music cassettes. The managers’ enthusiasm and desire to mimic the UK music market has slowly faded, and after the 1999 Russian crisis, there was no money left either.The final attempt by Bomba to promote and publish this sort of music was embodied in the modern rock band SH…. Despite the impressive quality of recordings, especially for that time, powerful advertising campaign and critics’ acclaim, nobody bought the band’s records and it became obvious to everyone that there is no business in guitar music.

Travels in the desert

Following the crisis in Russia, the place of the naive romantics and idealists in the Lithuanian media and music business was taken over by the money-smart cynics. Radio stations that played Lithuanian music, such as Lietus and Pūkas, cleaned their nets from rock music which did not fit the format, and TV stations also no longer gave in to band requests to play live, preferring instead synthesisers. Even professional pop music promoted by Bomba had less and less space as it was replaced by Russian restaurant popmusic authors. Journalists also stopped writing about bands that a few friends liked and instead sang praises to popular pop artists. A new scene began to be created by television, as TV concerts and reality shows became the only way to introduce new bands.

Rock bands found themselves in a position where they had to either adapt to the times or limit themselves to the underground. Bix, Skylė and Siela disappeared in the underground alongside all the new rock bands. Biplan softened their original sound to wedding music level, ŽAS started writing restaurant pop chants. Only the creative force behind the face of Foje, Andrius Mamontovas, survived having gained the national icon status. New bands would spend a long time on niche scenes – small sung poetry or metal events. It became virtually impossible for new rock bands to gain any popularity: the radio refused to play their music, TV refused to show them, the internet was not a very popular place to listen to the music and managers showed no interest. Instead of new rock musicians, each year saw the emergence of participants of various reality shows, one of whom necessarily had to be a rocker (the other a rapper). Neither nu metal, nor the revival of the New York garage rock at the start of the new millennium, nor even emo reached Lithuania – not a single radio station played anything in which the guitar sounded differently from the ways it did in the 1980s. Similarly to what happened in the 1970s, rock music was pushed out even from the counterculture – stylish youth listened instead to electronic music, traditionally strong in Lithuania.However, even in this desert, there were some insurgents. A punk from Ukmergė under the name of Psichas and the sentimental punk rock band Requiem used to fill in quotas allocated to rock at various events, but the band managed to not succumb to the wave of wedding music. IR (later Perfect Pill), probably the only prominent Lithuanian band of alternative rock, used to appear on the little-watched Baltic MTV channel, while the most notable rock debut of the decade was the Lithuania’s tongue in cheek performance at the traditionally pop-dominated Eurovision contest in 2006 created by Gravel. Inspired by the music and behaviour of the Gallagher brothers, the Sinickis brothers’ band was probably the only politically incorrect breath of fresh air in the culture of predictably arranged restaurant music.

The revival

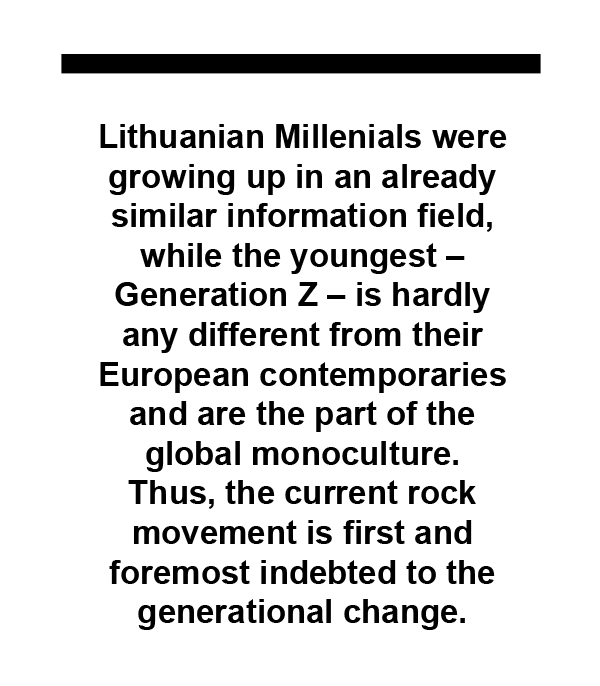

Musical taste is formed in one’s youth and reflects the music taste of an entire generation. Lithuanian Baby boomers (born in 1940–1960), instead of Lennon and Dylan, listened to Povilaitis and Nerija restaurant pop; Generation X (1960–1980), having briefly tasted modern music, was soon led into the thick woods of pop. Those generations had a difficult Soviet experience, they grew up in a complex information field and differed greatly from their peers abroad. In contrast, Lithuanian Millenials (1980–2000) were growing up in an already similar information field, while the youngest – Generation Z – is hardly any different from their European contemporaries and are the part of the global monoculture. Thus, the current rock movement is first and foremost indebted to the generational change.

The 2009 financial crisis affected Lithuania particularly strongly: in the first quarter of the year, the country’s economy shrank by one fourth. Wages were decreasing, many people lost their jobs and a massive wave of emigration began. However, it was during that year that cheaply, yet stylishly furnished bars began pop up in city centres – first of all, in Vilnius – that attracted very young audiences. Gringo, Pianoman and their countless followers poured beer, made street food and played rock, while their clientele were young programmers, startuppers, managers and advertising professionals. The new generation had matured and very soon it will be them who will make up the majority of festival-goers, and with them in mind music clubs will be opened and music will be written.The most important musical era did not come to be out of nothing, but rather its arrival was secured by godfathers who were more idealists than entrepreneurs, just like Bomba before. The free magazine Pravda gathered around itself the best journalists from among the trendy kids of Vilnius and dictated fashion long before the advent of FB and Instagram. It was Pravda that wrote about and curated modern music: its Newbie awards created a counterweight of counterculture to the hierarchy of pop music formed by radio stations and television.

Another important factor was the launch of the state radio's third programme that was dedicated to alternative music. Opus 3 (now LRT Opus) has never had a huge audience, but people who love alternative and rock music now had a starting point, a playlist, while musicians had a station that will play pieces with a different sound than the format.

Flagships of this new musical era have become Freaks on Floor. Thanks to its catchy music and smart self-promotion, this solidly forged duo of modern post-grunge and garage rock quickly became the most recognisable rock band in Lithuania, for the first time in thirty years pushing out from that position such veterans as BIX and Andrius Mamontovas.

Following in the footsteps of Freaks on Floor soon was a band from Šiauliai Colours of Bubbles who played clear-cut British rock, while the band ba. caught the imagination of the younger generation the most. The musical influences on the Kurt Cobain-channeling frontman Benas Aleksandravičius range from modern electronic music to the 1970s post-punk, however, that appears to be much less important than his performance – each concert of the band delivers an explosion of energy. The revivalists of psychedelic music Garbanotas and the dark post-punk electronic music band Solo Ansamblis, which should absolutely be regarded as part of the rock scene, are other names that have grown in popularity over the past few years.The Garažas competition held by the club Tamsta has been incubating a new wave of popular youth bands for several years in a row – currently the most popular alternative music bands such as ba. and Solo Ansamblis started their careers there, and were followed by Pilnatys, Timid Kooky, Abii, Abudu, Jauti and Flash Voyage.

Unlike previous projects, these bands do not die – they find their listeners who fill clubs, courtyards and small alternative festivals in Vilnius and Kaunas. It is the music infrastructure that is the fundamental difference from the past rock peaks of the late ’80s and ’90s. There are radio, bloggers, influencers and music media, as well as clubs, city festivals and music festivals (even the big ones find room for rock). Local rock centres are being re-established in Klaipėda, Alytus and Ukmergė, and the scene is no longer dependent on Vilnius alone. The new rock heroes are always able to attract enthusiastic audiences in their thousands but are not yet ready for stadiums or even arenas. Nonetheless, they should find it hope-inspiring that arena tours are successfully sold out by their older colleagues. Andrius Mamontovas and Marijus Mikutavičius, a TV host who likes the 80s stadium rock, do just that every two years. And, finally, Devilstone, the festival that has mutated from metal to wider rock, has become the place for reviewing the scene and setting new conjuncture.

The sound of Vilnius

The Lithuanian electronic music scene is a proud province of Europe – it has a glorious history (Vilnius’ club Gravity and Kaunas’ EXIT have been mentioned internationally), a handful of DJs and producers like Happyendless and Leon Somov are known on the international scene, while Ten Walls and Manfredas perform at international music festivals. Last year, the first little eagle – the European EDM starlet Dynoro – was hatched. In comparison, the last Lithuanian rock band to be noticed abroad was BIX in the early 90s – since then, the rock music of the country has been largely created for local consumption. Even in the experimental black metal scene, led by Au-Dessus, Lithuania is a bigger name than in rock.

The story explains itself: the many ups and downs, little space to play in, insignificant interest, no money. Rock is not the music for records but performance and it requires not only rehearsals but regular concerts so the musicians could improve their stage and instrumental skills. A small market dictates small ambitions. Why experiment and unnerve your audiences if you can copy and become the only Lithuanian Arctic Monkeys or The Killers? It is not surprising that the fashion, art, theatre and poetry scenes collaborate more with electronic music producers than with rock musicians.

When it comes to small markets (like in geographically close to Lithuania countries Estonia or Iceland), international promoters are looking not for yet-another-band-that-sounds-like-arctic-monkeys, but for curious, different sonorities. It is not separate bands that get exported but scenes – several similar groups that influence and pull each other up. Does Vilnius have such a scene? Definitely not.On the other hand, in recent years Lithuanian rock has come closer to it than any other genre, and there have even emerged two trends that should be noted. First, it is the local musicians’ disproportionate love for post-punk. A surprisingly big number of bands are exploring the musical legacy of The Cure and Joy Division, incorporating it into electronic music, pop and metal. This love is rather contextual: ba. and a few other bands fit perfectly into the British punk / post-punk revival of Shame and Idles (minus political activism), while the Solo Ansamblis is part of the international darkwave scene. Popular bands are followed by debutants, and aspects of the genre are semi-subconsciously incorporated into other styles of music.

Another direction is related to Joneikiai brothers' quartet Garbanotas, which became the most influential band of the scene. The debut of these musicians from the suburbs of Vilnius who have listened to a fair share of Local Natives, Tame Impala and, most importantly, Led Zeppelin equalled a bomb explosion in Lithuania. According to local legends, the debut concert of the brothers broke records even in Klaipėda, a city which is not generally known for their benevolence towards rock musicians. The dreamy voice of Šarukas Joneikis lies on solidly built rock reefs and spreads the love for psychedelic culture and music of the 1970s. Although the band itself does not announce any strong manifests and its image remains distinctively modest, Garbanotas has captured the hearts of the younger part of Generation Y and is often presented as the most typical new rock band.After its debut, Garbanotas essentially created a niche for listeners of such music, and for the first time in Lithuanian rock history, one band is followed by so many others: Abudu, Flash Voyage and even Pilnatys are undoubtedly influenced by the sound of Garbanotas and often appeal to the band’s fans. What makes this scene particularly attractive is the fact that hippy psychedelics and guitar pop were played by most of the bands who were dispersed after Kalanta’s self-immolation. So – has the wheel almost turned full circle?

Autopsy report

Rock music in Lithuania was killed by the Soviets following the Kalanta-related events in 1972; the deceased showed some signs of life in the early years of independence but not for long, and once Foje disbanded, the musicians scattered to basements of various sizes. At the end of the millennium, the Bomba recording studio was trying to create a new, modern pop and rock scene, but the Russian crisis of 1999 extinguished every last bit of enthusiasm for many years to come. The eight-year-long drought began to subside at the end of the decade; over the period of ten years, with the help of LRT Opus, Youtube, FB and Instagram, the next generation have formed a small but fairly active rock music scene.

For the first time in thirty years, rock in Lithuania has listeners, infrastructure and talented bands. It is a heavily niche genre that hardly reaches beyond the audiences of LRT Opus, Start FM and Classic Rock FM radio stations as well as niche Spotify playlist listeners, but the bands gain recognition at various awards and play a certain role in the creative industries. The rock scene is an important part of an alternative youth culture that does not aspire to appeal to the taste of the masses. As in the rest of the world, the guitar rebellion in Lithuania is taking place on the fringes (or is possibly even dead). Nowadays teenagers prefer to rebel with cheap Fruity Loops samples and Auto-tune box, but if we look at the amount of movements, rock music probably had the most throughout history. If it is a wooden overcoat, it is comfortable enough. And when another Jesus of guitar music comes in the shape of Kurt Cobain, the four Beatles or John Lydon, the monster that is the ‘eternal lie’ will rise again.

Translated from the Lithuanian by Julija Gulbinovič

[1] Mykolas Katkus is the vocalist of the band The Station.