Reinhard Oehlschlägel. Out of Lithuania

A (West) German music journalist’s impressions of new music from Lithuania

The so-called avant-garde of composers is not always in the vanguard of political, social, or cultural developments – as the originally military term suggests – but this does sometimes happen. It is however by definition impossible for observers such as journalists, who report on these developments, and academics, who work slower and study them in greater detail.

One of the many regions of the world and its culture can be observed from many different places and at very different times. So readers who experience the same music from Lithuania as I have – but from a very different perspective or from a greater distance or much later – may consider very arbitrary and random what I write below.

There is also another expectation connected with such endeavours that is often disappointed; especially composers expect more or less critical observers to possess a kind of unadulterated objectivity. This is strictly speaking a paradoxical expectation since most composers demand the right to absolute subjectivity in their own work, and rightly so, in my opinion. But they forget that their highly subjective compositions are experienced in concert halls or wherever by individuals listening in very personal and subjective ways.

Not just art itself is free; the perception and interpretation of art is also free. This already follows from the statement’s inversion: If all musicians and listeners interpreted in only one way objectively predetermined by the composer, we would have an incredibly one-dimensional and ultimately extremely boring reception situation that could even be fatal to the work of art. This of course does not question the need to strive to interpret the work in a way that is as close to the composer’s intentions as possible. The following text therefore assumes the existence of a truly independent subjectivity of observation and interpretation.

After studying in Hanover, Göttingen, and Frankfurt, I spent a few years learning the trade as a freelance and “permanent freelance” music journalist for the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” and the “Frankfurter Rundschau”. From 1972 to 2001, I then worked as the new-music editor for Deutschlandfunk, the 24-hour German national information radio station. This at first had almost no studio production capacity, but starting with the debut concert of the Ensemble Modern in October 1980, it sometimes organised concerts and studio productions.

Deutschlandfunk was established by a in 1962 and assigned the task to provide comprehensive information about Germany, which until October 1990 meant both West and East Germany. Because the two parts of Germany were integrated into the antagonistic NATO and Warsaw Pact systems, Deutschlandfunk’s mandate of course also included providing extensive information about the countries in these alliances.

Since October 1983, I have also participated in the founding and management of the journal for new music “MusikTexte”, which was and is mostly based on texts of various German and other radio stations.

There were no problems or restrictions [difficulties] at West German radio stations in reporting on new music events, institutions, and musicians in West Germany. The same was true for Western Europe, but not until 1980 were there justifiable reasons for investigating North and South America.

Journalistic investigation was much more difficult in the former East Germany, and even more so in the eastern neighbouring countries and the huge Soviet Union. We had to start from scratch, so to speak, in getting to know new music from Lithuania as well as most other Eastern Bloc countries except Poland and in transmitting it to the Deutschlandfunk listeners in East and West Germany.

This of course does not mean that the appreciation of new music within the Eastern Bloc countries or of new music from these neighbouring countries started from scratch. Lithuania was readmitted to the International Society for Contemporary Music by re-establishing the membership that had already existed from 1937 to 1940. This was a symbolic way of showing that the years of foreign domination had not been able to prevent Lithuania’s development.

In connection with the return of the music of around 1900 by for example Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Franz Schreker, Alexander von Zemlinsky, and Ferruccio Busoni into musical life in Germany, a Soviet Melodiya record from 1981 first introduced me to Lithuanian music in the form of the symbolist [symbolistic] symphonic poems Jūra (“The Sea”) and Miške (“In the Forest”) by Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis with the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra under Juozas Domarkas. I must have acquired this record in a music shop in East Germany. Previously, I had only heard about the role of the Lithuanian George Maciunas around 1970 in connection with my investigations of Neo-Dada and later Fluxus art in Germany and the USA, but I had never heard any of his Fluxus pieces.

During the 80s, the first steps were taken in West Germany to get to know Lithuanian music and to acquaint the public with it. For example, a network of music journalists interested in new music was slowly but steadily forged. And the musicologists Dorothee Eberlein and Krzystof Droba, who are experts on Lithuanian music, were convinced to prepare the first broadcasts about Lithuanian music on Deutschlandfunk. (About Bronius Kutavičius on 16 March 1988 and about new Lithuanian music on 26 July 1989; the print versions of the broadcast script are in issue 28/29 from March 1989 and issue 42 from November 1991 of the journal MusikTexte; issue 36 from October 1990 also has an article on Vytautas Landsbergis and Lithuanian modern arts.)

|

|

At the beginning of 1992, all my colleagues at Deutschlandfunk and I received our director general’s request to add programmes about the three Baltic countries Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia to our normal order of programmes during three consecutive weeks from late March to early April. So I contacted the people I had met the previous autumn in Vilnius. I was able to invite a Lithuanian ensemble to our chamber music hall in Cologne to present Lithuanian music to the audience in the hall and to our listeners throughout the slowly reuniting Germany.

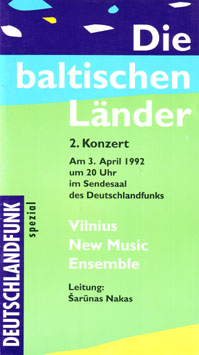

The primary impulse was to give young Lithuanian musicians the chance to come to the West for the first time. I had already previously experienced with composers from East Germany that this was the most important thing at first after having been more or less locked up for decades behind the Iron Curtain. I chose the Vilnius New Music Ensemble under Šarūnas Nakas based on a recommendation by Bronius Kutavičius, in whose music I had become interested in Krzystof Droba’s radio programme.

Programme for a concert of Vilnius New Music Ensemble in Köln (1992) |

And so one of the first concerts in West Germany with Lithuanian music was performed on April 4, 1992. Not just the journey of more than 1500 kilometres in a minibus by the eleven Lithuanian musicians with their concert and folk instruments and their concert clothes and folklore costumes was an adventure. The concert in the Deutschlandfunk studio also proved to be an adventure. It included two key works of contemporary Lithuanian music of the older generation, namely two of the “fantastical reconstructions” composed by Bronius Kutavičius based on the few preserved Indo-European text fragments, his Magiškas sanskrito ratas (“Magic Circle of Sanskrit”) for an ensemble of 12 vocal and instrumental soloists and his oratorio Iš jotvingių akmens (“From the Jatvingian Stone”).

The contrasts in the programme consisted of Chopin-Hauer for instruments, voice, and tape by Osvaldas Balakauskas, the “universalist” among older Lithuanian composers, and the homage to Paul Klee Čiauškanti mašina (“Twittering Machine”) for piano and tape by Rytis Mažulis, who is about 20 years younger. The younger generation was represented by Paukštis ant balso šakos (“A Bird on the Voice’s Bough”) by Šarūnas Nakas, the director and conductor of the Vilnius New Music Ensemble, by Lydermė for voice, viola, and tape by Rasa Dikčienė-Zurbaitė, one of the ensemble members, who were all young composers, musicologists, vocalists, instrumentalists, and actors.

This concert of course impressed me very much and reinforced the impression that Lithuanian music and its austere beauty, its peculiar appeal, and its variety of very different personal styles had made on me at the previous autumn’s GAIDA Festival.

In August 1993, the Helsinki Festival under the direction of the opera singer Veijo Varpio was able to present a comprehensive Baltic states programme after a similar plan by the German Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival had failed due to lack of financial support. The programme included a Baltic Music Symposium by the music semiotician Eero Tarasti in the musicology department of the University of Helsinki, in which Lithuania was represented by Ona Narbutienė and Jonas Bruveris and the composers Onutė Narbutaitė, Bronius Kutavičius, Osvaldas Balakauskas, and Juozas Širvinskas. And the concert halls of Helsinki and Espoo were filled with an incredibly varied selection of new music from Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland, including a marathon concert with mostly world premieres of commissioned works.

“During the transition from a state socialist planned economy to a liberal market economy in the East European countries, nothing is more important (for the musical life of a country) than commissions and invitations to Western countries.” (Deutschlandfunk, Musikjournal on August 27, 1992) Lithuania was represented in the marathon by Žiemių vartai (“Northern Gates”) by Kutavičius, by Polilogas (“Polylogue”) by Balakauskas, and by Piešinys styginių kvartetui ir sugrįžtančiai žiemai (“The Drawing for a String Quartet and Returning Winter”) by Onutė Narbutaitė.

In contrast to the new pieces by Latvian and Estonian composers, these pieces could only be perceived with difficulty as being specifically Lithuanian; they were too colourful, too different, too full of variations, even too individual. But in comparison to the two participating Finnish composers, almost all of the participating Baltic composers seemed to write more succinctly, sensitively, and artificially. These Baltic composers presented a very significant enrichment of new music in Europe, less through new experimental, technological, electro-acoustic, or similar aspects than through their tradition-conscious, religious, minimalist, and archaic qualities and their high degree of integrity.

Since then, music by Lithuanian composers has become a completely normal part of my and certainly not just my concept of Central European music. But there have of course been high points such as the following: planning the journal MusikTexte with a series of articles by the Lithuanian musicologist Ramunė Kazlauskaitė about Narbutaitė, Nakas, and Mažulis, listening to concerts at the 1993 Warsaw Autumn festival, in the series Musik der Gegenwart of the radio station Sender Freies Berlin, at one of the internal festivals of the Münster Music Conservatory, at the festival Frau Musica Nova in 1998 in Cologne, at the MaerzMusik festival of contemporary music and its focus on the Baltic countries, and last but not least, for several years already at the World Music Days of the International Society for Contemporary Music. This festival will be organised for the first time by the Lithuanian section of the ISCM, and in accordance with ISCM festival tradition, the hosts will present a rich sampling of their own composing abilities to the guests from all over the world.

Translation from German by Ekhart Georgi

World New Music Magazine Nr. 18