Kudirka talks to Kudirka

- Jan. 15, 2025

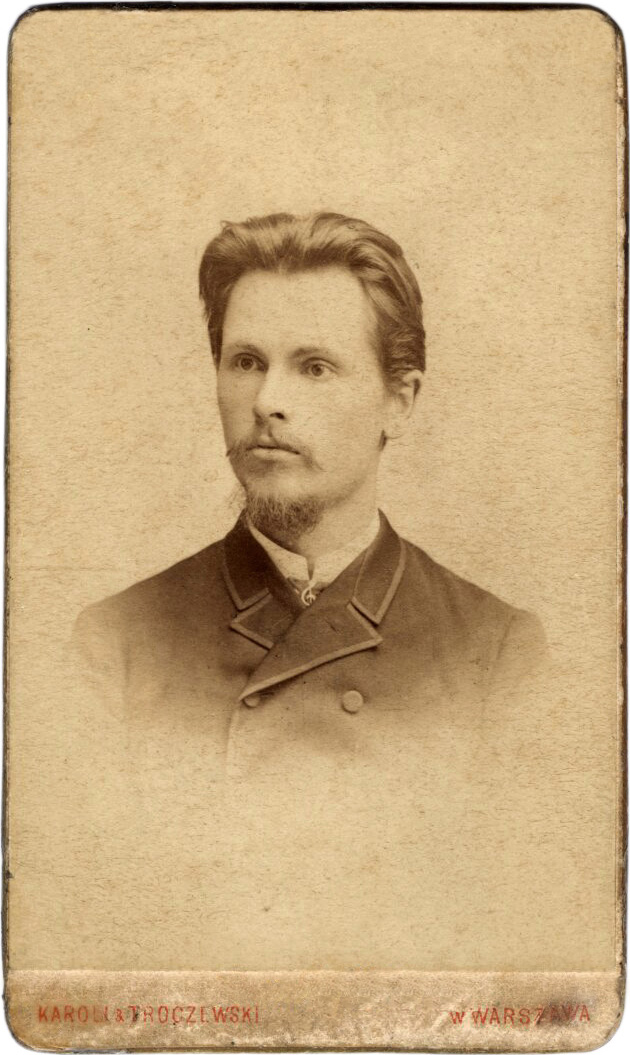

Joseph Kudirka is a composer and performer of experimental music. He was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA, in 1978. He has, at other times, also been a legal resident of the UK and Switzerland. His works have been commissioned and/or premiered by musicians and ensembles, including Rhodri Davies, Daniel Plöger, Anton Lukoszevieze, Mark So, Phillip Thomas, Zinc & Copper Works, Wandelweiser Komponisten ensemble, Edges ensemble, and Ensemble Neue Horizonte Bern. As a double bassist, he has premiered works by numerous composers, including Michael Maierhoff, Antoine Beuger, and Eva-Maria Houben. Joseph Kudirka is a member of the composers' aesthetic movement Wandelweiser.

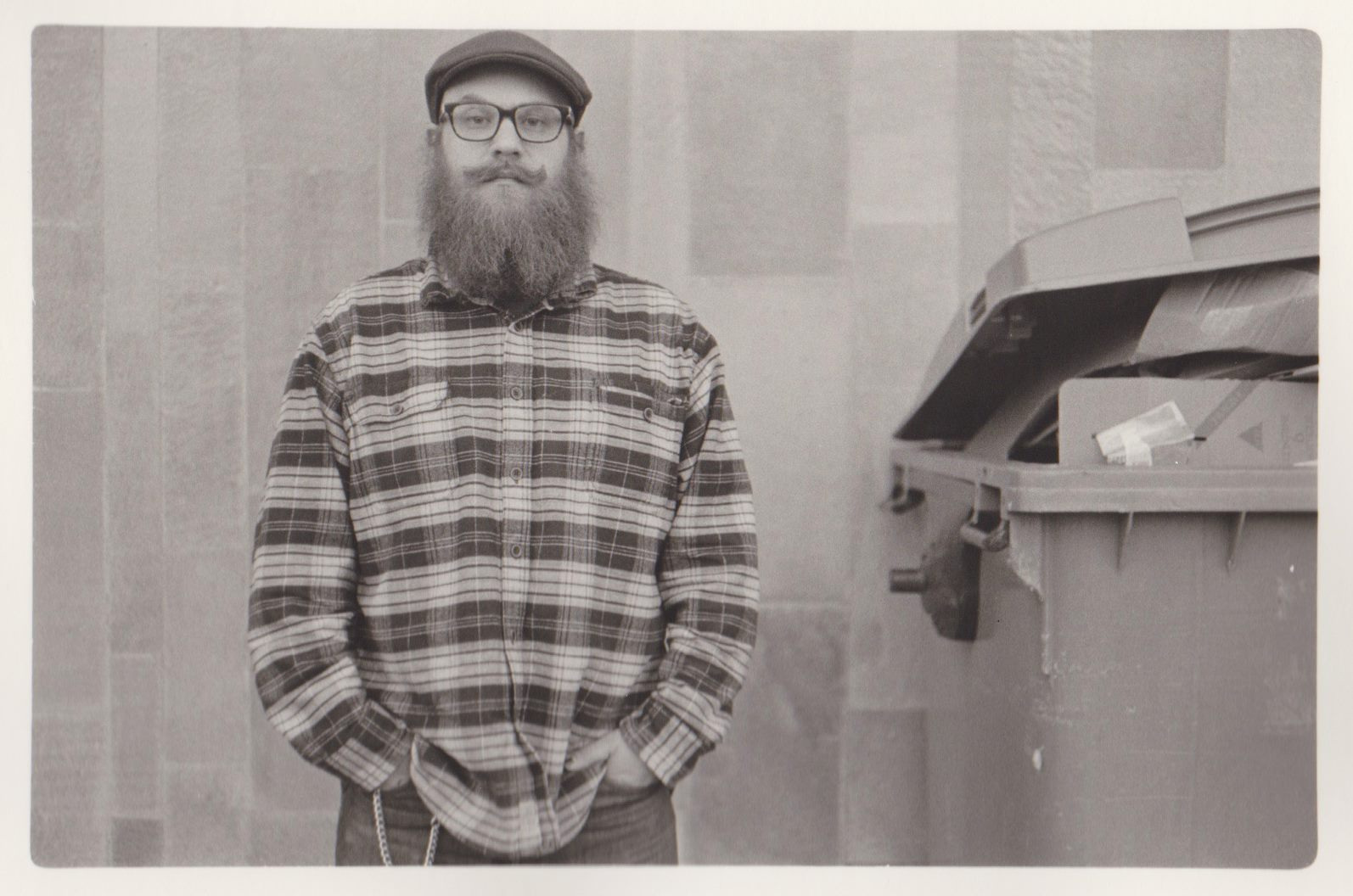

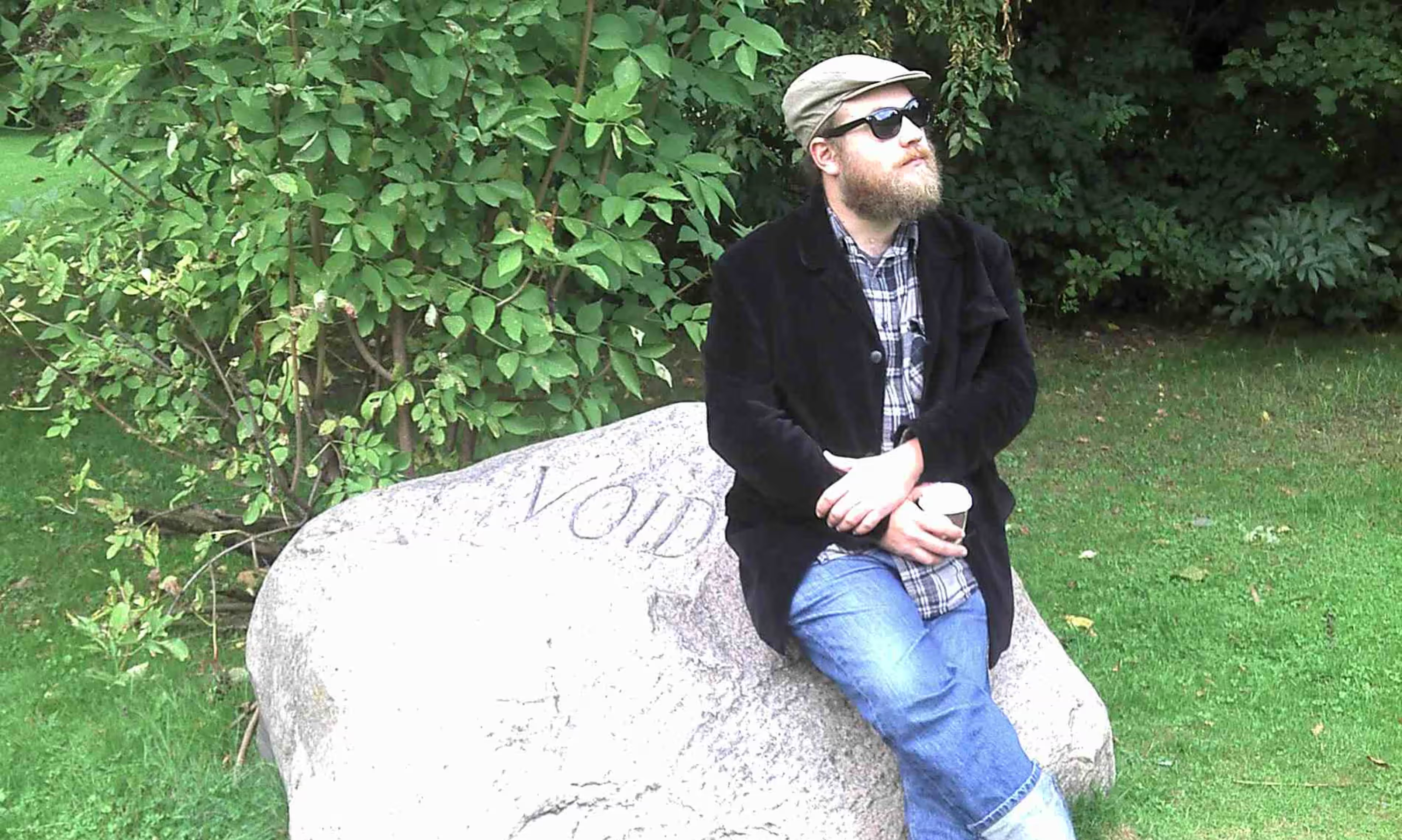

Žygimantas Kudirka is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, and performer working in the fields of interactive fiction, speculative science fiction, artificial languages, and avant-garde rap. Kudirka’ work spans exhibitions, immersive installations, theatre, and audiovisual performances. Known for his innovative approach to language, the artist is constantly searching for a universal dialect that would be understandable to plants, animals, babies, and future links of evolution. He has released 8 albums of music and a book of interactive poetry. Represented Lithuania in the European Slam Poetry Championships and was recognized as the best performer in the genre in Europe in 2014. Leads collective writing workshops. Has received numerous awards in music, advertising, visual arts, and literature.

These are the excerpts of the 6-month dialogue via emails between the two.

Kudirka talks to Kudirka about Kudirkas

Ž. K.: Dear Kudirka,

It's me, Kudirka. It happened that I discovered you. Not sure, if we share the same blood, but at least we carry the same surname. That seems to be intriguing!

I'm an artist, writer and musician myself and I think it would be interesting to hear from you. A form for our acquaintance could be an interview. Kudirka's interview from Kudirka. What about that?

J. K.: Labas, Žygimantas!

It's nice to meet you. I also wonder if we're related; I've never met a Kudirka outside of my own family. It's curious to me that you find it interesting, because it's my experience that the younger Lithuanians I've met (those who grew up in the republic), aren't interested in the diaspora; they wonder why these foreigners who can't speak their language call themselves Lithuanian, and perhaps even find it insulting.

Ž. K.: It’s strange that young people aren’t interested in diaspora. Seeing how your natives adapt elsewhere, especially ones carrying the same surname can lead you to interesting discoveries. Maybe it’s because of the age difference.

Now I reside in Vilnius, Lithuania. Do you have actual Lithuanian roots, how are you related to this country?

J. K.: So, yes, my family has Lithuanian roots, but I don't know a great deal about it. My father's grandfather (his name was Joseph, and I'm named after him) came to the US sometime before 1905 (the year my grandfather was born in Chicago). Family legend is that Vincas Kudirka was his uncle, but I have no idea if that's true; in my family, words like "uncle" and "cousin" can mean quite distant relations. What history I know is probably a combination of truth, legend, and pure speculation. My grandfather was the last person in the family to speak Lithuanian (his mother was also from there), but he died before I was born. His name was Paul Napoleon Kudirka. My father says that this was because our family was originally French, but my uncle John said it was because "grandma was crazy."

Ž. K.: Grandma is not crazy!

Our French roots are supposedly true. The story is that Kudirkas came to Lithuania with Napoleon‘s army and one soldier decided to make love instead of war. However, the most interesting part of it is that in the old Provencal language couderc means “grass” or “lawn”. And that explains to me a lot about myself. It brings up so many lighthearted associations! How does that correlate with your character?

Here's the evolution of our surname: Couderc > Kuderk > Kuderka > Kudyrka > Kuderkevicz > Kuderkowicz > Kuderkevičia > Kudyrkewicz > Kudirkewiczius > Kuderko > Kudirko > Kudirka

J. K.: Does anyone really know if this French story is true though? It seems kind of crazy. I mean, some guy deserts Napolean's army in 1812, and – at most – two generations later, a man is born who becomes the champion of Lithuanian language and culture.

As far as my father's stories go, his grandfather grew up speaking French at home, and named his son Paul Napoleon... I don't know which possibility is more crazy. Really, I would like to know the actual history. Is it something that Lithuanians know, or is it just made up? I mean, history is all made up anyway.

I would like to know more about the surname though. What I had heard/read is that most Lithuanian surnames worked this way – something phonetically translated from other languages, spelled as they would sound in Lithuanian. Is that true?

I'd heard that many were Greek, because when the church came, they were orthodox, and they couldn't believe these pagans didn't have surnames, so they just had new surnames that didn't really mean anything – essentially gibberish. Of course that was hundreds of years ago, so who knows...

But it was more recent in Mongolia, and that story is really interesting.

Ž. K.: Talking about a phonetical translation of surnames – wouldn't be so sure about that. I think it's a speculation. Especially things related to Greek surnames. Greeks have similar endings of words – that may be the reason the names and surnames sound so native to Lithuanians.

J. K.: I don't know if it's true, but I like the story. I like to think of an entire country of people named after something that sounds like a Dada practice. I also like that my name means "grass" or "lawn", because that's incredibly boring, and I love boring. Boring is the best.

I looked up your name – it seems like you do interesting things! Is there a place I can hear any audio of your work?

Ž. K.: Many years ago I wrote a poem about different Kudirkas scattered around the world. You can listen to it here.

(it’s quite low-fi, but you can listen to phonetics)

I’ve also published an interactive poetry book XXI a. Kudirka (XXIst century Kudirka). Here you can find some of my poems in English.

That’s an early video I’ve made – a list of the most sexy English language words rearranged so that the voice robot would read it as a poem.

And this one is a collaborative piece with a few other brilliant artists Robertas Narkus, Jokūbas Čižikas, and Adas Gecevičius – a nature-sci-fi musical filmed entirely by drones.

J. K.: Thanks for these pieces! I like them! It's crazy how you can now make videos for not much money that would have only existed in expensive films twenty years ago.

Ž. K.: Yes, same with music. I really love the term ‘bedroom producer’!

Of course, there's much more to tell you about me, but let's focus on Kudirka’s on a wider scale. Do you know any famous Kudirkas except Vincas? Are they into music?

J. K.: Well, there was the one in the 70's or early 80's who was a bit famous in the US, because he jumped off a boat.

Ž. K.: Jumped the soviet boat to an American one!

J. K.: I don't think he played any instruments though. My cousin, Michael Kudirka, is an excellent classical guitar player. I don't know if he's famous, but he's probably more famous than me. Still, it was nice that he told me a story that last year when he was giving a lecture at a university, a student asked if he was related to me, because that student really liked my music. His mother is a classical pianist and organist, but she's not a Kudirka by birth. Supposedly, my grandfather played some kind of horn in a jazz band, but that's all I know about it. You're probably more famous than me!

Ž. K.: Well, talking about music, my cousin is a piano player, grandfather invented some kind of panpipe modification. Also, while researching Kudirkas on the internet for the aforementioned poem – I found Joseph who’s an organist and choir leader (so many Josephs in our family), also – Justin, who even released a vinyl of some traditional Lithuanian instrument songs on Columbia Records.

What kind of music do you play?

J. K.: I simply say that I make experimental music. I don't make much distinction whether it's acoustic or electronic.

I play in a few groups, either playing acoustic bass, electric guitar, low-fi electronics, or objects. Sometimes we play pieces by me, sometimes we improvise, and sometimes play pieces by others. Sometimes I DJ at bars, where I play 7" and 12" records; mostly punk and new wave, but including some Detroit electro, some ambient music, etc.

I simply say that I make experimental music. I don't make much distinction whether it's acoustic or electronic. Most of the groups I play in now combine them somehow, but I would guess that much of my music is purely acoustic chamber music. I do have some electronic pieces, of course. This one was made as an electronic piece, but includes lots of acoustic sounds, from field recordings.

As for how I got into doing it, it was simply a natural progression from studying music. As a teenager I studied bass (and started to get involved with electronic music) and played in different kinds of bands, then went to university to study to be an orchestral double bassist. During university, I switched my focus from performing to composing, and started doing more electronics – that's where I started the electronic duo, bunnyhug, that I was in for five or six years, total, I think.

Actually, we never really broke up, and still talk about maybe making another record or playing again, but it's just logistically difficult – we each have other lives now.

Ž. K.: What are the venues you play music in? Is it formal, academic venues for strange music, or strange venues for strange music? Or maybe you play only in bat caves but don’t consider your music strange at all?

J. K.: As far as venues, it's all of those things. I don't really think about my music as strange, just because this has been my focus for so long, so I'm part of a community where I'm just another equal. When everyone's making strange music, it's not so strange anymore.

Ž. K.: Talking about strangeness, isn’t it strange to give an interview to Kudirka?

J. K.: Yes, it's a bit strange to give an interview to a Kudirka. I've never met a Kudirka that isn't closely related to me. When I was in college, in Chicago, I found another Kudirka at another university there (maybe even another Joseph Kudirka). I sent him an email that said something like, "There can be only one," but he didn't write back. How about you? Presumably, you've now talked to several other Kudirkas. Growing up in Lithuania, did you meet Kudirkas outside of your family, or have you had to seek them out?

Ž. K.: There are a few more interesting ones. For example, Robertas Kudirka is a serious academic who has written a dictionary of profanity in Lithuanian, that was written by using a kind of method acting tactics – dealing with all the margins of society such as criminals or drug users personally. Or Raigardas Kudirka is one interesting surrealist painter obsessed with American urban landscapes, although he lives in Vilnius.

Genes genes genes. Can you see some parallels between your life or attraction to specific things and Vincas? I just noticed, that my past job in various magazines, an interest in poetry and music in a way overlap with things Vincas did. Although obviously, that was not a conscious choice to follow the ways of Vincas. Vincas is not my Buddha.

J. K.: Well, I like that he was a radical and rebel in some ways, and I would like to think of myself as a radical and rebel in some ways. I wouldn't mind if my face was on money, even if it was to be replaced by the Euro, though I'd prefer a world where there was no money at all, and bills were reserved for museums and burning in furnaces, to heat homes during the winter. Maybe they could be shredded up to make new paper to write pieces of music and poems on.

Ž. K.: What do you think about the Lithuanian national anthem purely as a composition? (Let's leave its unifying aspects, function and meaning aside for now)

J. K.: I really like the Lithuanian national anthem! I think it's a good piece of music. On the one hand, the basic melody is quite simple and memorable, but there's more harmonic complexity than in a lot of anthems, so it stays interesting. I think it's a good piece/song.

Ž. K.: Enforce Vinca’s legacy or promote newborn Kudirkas?

J. K.: Oh, I like history. I like children too, but I don't care if they're called Kudirka. My sister has two children, but they have their father's surname. Both of my cousins who are Kudirkas only have daughters. We don't need more Kudirkas. Besides, they'd only steal our thunder, Žygimantas! We can be the last generation of Kudirkas, and that's fine with me. The history books will remember.

The text could end here... But! It seemed to be valuable to share a reference-rich excerpt from a conversation about musical influences and compositional principles.

Kudirka talks to Kudirka about music

Ž. K.: What is your chronology of music genres you used to listen to – from a very early age?

J. K.: I'll start off with a short chronology of the music that interested me. As a child, I listened to what was on the radio, but that was basically dictated by what my older brother wanted to listen to because he was the oldest of the three children.

My father listened to music that I hated at the time, but I like most of that stuff now: Joan Baez and Willie Nelson are the two I hated the most and now really love, especially Willie Nelson. I don't know if I like that music now in part because my father listened to it, or if I just grew up to have better taste in music.

So, I listened to what was on the radio in the US in the early 80's. A lot of it was English music. I remember that I really liked The Clash and Madness, and Culture Club, but there were other things that were really garbage that I also loved – songs like "eye of the tiger." It's easy to go through one's personal history and only mention the good things, and ignore the embarrassing parts.

When I got my first cassette player, the first three tapes I had were Living Colour, Guns 'n' Roses, and Skid Row (Skid Row is the embarrassing one, for those keeping score).

So, that was the late 80's, and I was into hard rock and heavy metal music, but also always interested in "classic rock" music, like Led Zeppelin (who I hate now, for being criminal cultural imperialists), Pink Floyd, The Doors, The Who, The Rolling Stones... including The Grateful Dead, who were really weird, and actually did free improvisation and things.

That led to the late 90's, when I was interested in jazz fusion, progressive rock, and nerdy music like that. I mean, I really loved King Crimson, and lots of those 90's Japanese and Swedish progressive bands – oh, and things like Richard Pinhas/Heldon... I was a huge Ozric Tentacles fan. I had all of their albums, t-shirts, etc.

I was also still interested in those 80's bands. I really liked The Cure and Depeche Mode, for instance... and Echo and the Bunnymen.

I mean, you get into these things, and you dive down these strange holes of connections and knowledge. Maybe you buy a record from the 70's because of who the bass player on it was, and it's great – I think that's how I discovered Brian Eno's pop albums, even though I knew his name before – really, those pop albums he made are much better than any of the "ambient" music.

So... I was also interested in classical music, and I especially loved the music of Alfred Schnittke, and then Arvo Pärt, etc. In high school, I played in a festival of Henry Górecki's music, with the composer present, which I thought was great. In college, I just got into weirder classical and weirder pop music. I was really into Australian twee pop, at the same time I was really into Fluxus.

Maybe describing my musical life now just paints a better picture.

Ž. K.: I noticed that composers of rhythmic electronic music after a while move into the planes of drone and ambient – as it helps them think more spaciously about the sound. What is your experience?

J. K.: I don't think most people making what's called drone music really think about it that way. I don't really. I don't think it's about thinking about the sound as planes or anything like that.

I think it's basically because rhythm has very little to do with what's interesting about Western music, so getting rid of rhythm is just a way to trim things down – I think subtraction is the fundamental aspect of experimental music.

I mean, there is a lot of really great music where rhythm is important: Indonesian Music, Indian Music, West African music, Shona music, etc. Western music just developed differently, where rhythm wasn't the main focus. As great as Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven were, it wasn't because of their rhythmic inventiveness. The main thing that Western music really specialized in was harmony and secondarily (though primarily, probably for people involved in this "drone" music) timbre. What other cultures have something so complex in timbre as the symphony orchestra?

Of course, I'm being overly broad – there are fantastic timbral elements to Shona music, especially, but also Indonesian music, Indian music, etc., and there are great rhythmic pieces by Western composers too. I just wanted to give a broad answer to a broad question.

For me, personally, I don't think I'm making a drone piece or a piece that's not a drone piece. Each piece has a focus, and then I try to strip the other elements bare. So, some of my pieces involve lots of silence, some involve drones, some are very, very short, and some are very, very long.

Before any of that, I'm usually asking myself a question in music that I try to answer with music – considering the ontology of music from one angle is the question, and the new piece is the answer. (this is also a simplification, of course).

Ž. K.: You also play double bass. What is the contrast between double bass and electronics? Is the computer just another instrument?

J. K.: Well, a double bass is much, much larger than a computer these days. Decades ago, computers were much larger than double basses. That was the case when my former teacher, James Tenney, started making computer music.

I don't really think of the computer as just another instrument. It can be an instrument, but so can anything (I perform a lot with household objects and things found on the street). The computer is just an amazing tool, especially now that we have the internet.

My most recently completed piece was a string trio for a group in Switzerland. It's a purely acoustic piece, but the score was made with a computer and emailed as a pdf file. When working on the piece, I had to do some calculations about tunings (maybe this is a piece that would be considered a drone piece... it's all just long sounds throughout), and came across the website of a composer named Michael Norris, who I'd met years ago in CZR. He had some great online tools with tuning charts in them on his website. So, maybe someone who listens to these people playing violin, viola, and cello in Switzerland hear an acoustic piece of music, but I've only ever heard it as a wav file, and so much of it came about because of the computer.

Back when James Tenney was pioneering computer music, pieces were made with tape and punch cards, and tapes had to be sent around for people to hear the pieces.

And finally, another very interesting excerpt of the conversation about Kudirkas and Lithuania, including an audio piece created by Joseph Kudirka exclusively for this conversation – the way he imagines Lithuania.

Kudirka talks to Kudirka about Lithuania

Ž. K.: I sometimes introduce myself as Kudirka instead of a name. I find it somehow witty and provocative. Do you?

J. K.: I used to simply sign my scores "kudirka," which I perhaps thought was witty and provocative, but maybe I just thought it was a bit clever and minimalist – I mean, what other composer Kudirka was there going to be?

Now I sign my scores as Joseph Kudirka. I have found that people like the name. A girlfriend of mine pointed out that lots of my friends refer to me by my full name instead of just calling me Joe or Joseph or something, when talking about me to other people.

Ž. K.: Lithuanians definitely instantly recognise the surname. Have you met other Lithuanian artists on your journey of life (for example – Jonas Mekas)? Have you met other Kudirkas?

J. K.: I haven't met many other Lithuanian artists, like composers Rytis Mažulis and Justė Janulytė, but not well enough to say I know them.

I met more Lithuanians when I lived in England; I would tell them my name, and then we would talk and get drunk. Most of them weren't artists though.

Of course, I know who Jonas Mekas is, because of my interest in Fluxus, and then certainly George Maciunas.

My friend, Anton Lukoszevieze, a cellist and artist, is very interested in Lithuanian composers and artists, and he tells me about them and plays their music, but I don't really know them.

I would like to know more. I'm certainly interested if/when people want to say "hello."

Ž. K.: If Lithuania is mentioned in the news – do you turn the volume up?

J. K.: Oh, yes, I always pay attention when Lithuania is in the news. From an early age, it was instilled in me that my family was Lithuanian. There just aren't so many of us for it to ever be a big thing.

Where I grew up, there were lots of Dutch people, and tulip parades and things, and here – where my brother lives – they have a polka fest, and lots of people have Polish flags, etc., and in Chicago there are large Mexican and German celebrations...

Lithuanians? I never really remember anything big for us, until we watched that CNN footage while on vacation in 1991 – then Lithuania was in the news... and then we got the Grateful Dead-sponsored basketball shirts, and then... well, unfortunately, not so much since then. Maybe I should know more about the politics, culture, etc. I couldn't tell you what party is in power in government, for instance, or the names of the leaders and opposition leaders.

However, I still pay attention to those things in the UK, because I lived there for so long, and I have so many friends there – it was a big part of my life. When the Olympics are on, I root for the Lithuanians. I want to see them in the news, but these things go different ways.

Ž. K.: And the final question – how do you imagine Lithuania? Please answer this question by sound.

J. K.: So, for your last question, I'm afraid the answer has to be simple, because Lithuania – aside from what I know from facts and figures I read, and reading about the history, mythology, etc. – is just a romantic notion to me.

Realistically, I don't know what it means. So, I'm sending you this recording of what's going on as I type my answer to this question – I would imagine it will mostly sound like typing.

It's late evening here, and I'm sitting on my brother's porch, typing my responses to you. I'm drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. It's my brother's birthday tomorrow, so his wife is inside the house listening to music and baking him some treats.

I imagine that Lithuania sounds a lot like this – maybe the nighttime insects sound different, but I imagine it's basically just people talking to each other – even if just through typing – drinking, smoking, making food, having regular lives, etc.

Joseph Kudirka – Lithuania:

Projektą „Mic.lt tekstai apie Lietuvos muziką“ iš dalies finansuoja Medijų rėmimo fondas.